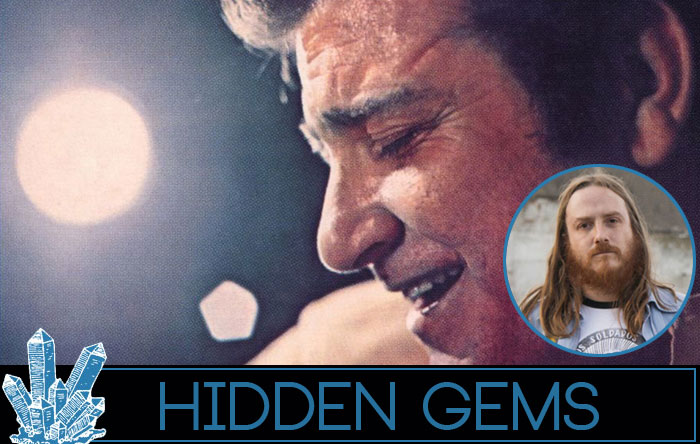

Nick Mitchell Maiato on Rusty Kershaw – Rusty…Cajun in the Blues Country

The new wave of Cosmic Americana brought in a lot of quality cuts last year, but one of my favorites had to be the debut from One Eleven Heavy —the softly choogled psych outfit that brought together members of Wooden Wand, Desmadrados Soldados De Ventura, Royal Trux, and Hans Chew. The band’s record shelves, undoubtedly stuffed with RSTB bait, seem like the perfect fodder to riffle through for the Hidden Gems feature. In fact, James from the band contributed a pick a little while back, long before things had solidified with the Heavy. So with their sophomore LP on the horizon I figured it was time to ask co-founder Nick Mitchell Maiato to dig into his collection and pick out a record that hasn’t cast nearly enough shadow on the majority of the listening public. He picked out a country classic, that, despite being a key Neil Young influence, hasn’t always been elevated to its proper due. Check out how the record came into Nick’s life and the impact its had on his songwriting.

Maiato muses on the moment that Kershaw’s classic found its way to his turntable, “Before I bought one of the only two solo albums he released during his lifetime, the masterpiece Rusty… Cajun in the Blues Country, Rusty Kershaw had long been a character within just a few degrees of separation of my own record collection. My friend, the Manchester, UK based guitarist and psychedelic folk singer Tom Settle, had covered Kershaw’s brother Doug’s electric arrangement of the traditional Cajun waltz “Jolie Blon” on his Tom Settle & Friends 2LP on my label Golden Lab in 2016. And our mutual friend, the avant-garde guitar player Jon Collin, later told me that he believed Rusty Kershaw ran with Neil Young’s crew right around the time that Young recorded On the Beach and, “wasn’t he the guy that notoriously turned Neil onto ‘honey slides’ [a potent concoction of sautéed, powdered weed and honey] during the sessions for that record?” Turned out Jon was right on both counts. Anyway, I personally discovered Rusty through the conventionally geeky contemporary record collector method of backtracking sidemen on other people’s records via Discogs.”

“I was (still am) going through a big Raccoon Records phase,” he recalls, “(the label run by jazz-folk-rock hippies The Youngbloods) a couple of years back and I’d gone down a bit of a Charlie Daniels rabbit hole. Prior to becoming the infuriating right-wing loon he’s known as today, or even undertaking his own successful career as a Southern rocker in the mold of Marshall Tucker Band or Lynyrd Skynyrd (but with proggier overtones), Daniels had chilled with the hippies, even produced a Youngbloods live album, and was a well-respected sideman who played a killer electric guitar and fiddle. (“Dylan loved him,” Chris Forsyth told me, recently, with more than a smidge of incredulity.) After singer-songwriter Jerry Corbitt left The Youngbloods, I discovered that he and Daniels had formed a duo and released some stuff. I also learned that Daniels had played guitar on this cool looking yokel-fusion record by a guy called Rusty Kershaw, Rusty… Cajun in the Blues Country. The overworked punning of the title seemed like it came from a deranged enough mind to be an interesting listen and the majestic layout of the front cover suggested some kind of Southern country rock royalty so I ordered a copy on a whim.”

“It’s always heartening to discover the roots of your favorite music. Like, in the 90s when I found out Stereolab owed it all to ‘krautrock’ pioneers Neu. And, if you’re a fan of Neil Young’s output in the mid-70s, particularly the albums On the Beach and, to a lesser extent, American Stars & Bars, hearing the opening track on R…CitBC, alone, will be little short of revelatory. “That Don’t Leave Much Time to Fool Around” is a rollicking half-time shuffle bemoaning the diminished energy of the hard-worn working class that, barring the plain speaking, lyrical content, could have been lifted right off of either of those Young records if it hadn’t been recorded four years prior to the earlier of the two. Rusty’s voice, however, couldn’t be more different to Shaky’s, having a rich, deep, chocolaty texture with Southern intonation that swells around the words: “Soon you’ll be a father/She’s in the family way…”

Digging further into what makes Kershaw’s album such a treasure, Maiato notes, “The ambitious stylistic scope of the album quickly becomes evident on the blistering electric blues of the second track, “This Day and Time,” which features subtly scorching Charlie Daniels fuzz guitar solos while drummer Karl Himmel (who later played on the song “Sail Away” from Neil Young’s Rust Never Sleeps album and went on to join Young’s International Harvesters band) is accenting all over the place and Rusty runs the gamut of his vocal range, quietly reaching to the source of his turmoil before crying out in pained falsetto at the crescendo, “Our day will come/Oh, Lord, yes it will!” It’s searing… deeply stoned… almost ridiculous in its expressiveness and one of those moments where music truly becomes some kind of extraterrestrial otherness that seems to exist independently of the humans through which it is channeled.”

“We’re brought crashing back down to earth with the goofy Cajun ode to Louisiana riverboat life, “Fisherman’s Luck,” which I can’t knock because it’s one of my wife’s favorite songs on the record, who intelligently maintains that the quality of a song should not be determined by the depth of its gravity (sample lyric: “I’ve caught everything from a turtle to a cat” – that levity enough for ya, darlin’?) And, if you’re a fan of Kershaw’s brother Doug’s work throughout the 70s and beyond, it’s one of three overtly Cajun tracks on the album that travels a similar path so should keep you happy. The other two are “Love City” and “The Country Singer” and there’s a degree of hilarity to the transition between these two songs, which run consecutively, as they’re almost identical, rhythmically, so as one ends and the next begins, there’s a kind of Groundhog Day moment where you’re like, “wait a second…” That said, the latter is a deeply affecting backwoods exploration of the meaning of being a country star and how celebrity doesn’t translate to a level of satisfaction that only companionship can bring and its lyrical refrain, “I got a new guitar, I got my name in lights/Why can’t I hold you tight?” says it all.”

“As well as featuring killer fuzz-wah trills from Charlie Daniels, “Keep on Trying” (like the album’s penultimate song, “Bad Luck Blues”) shares funky blues traits with John Lee Hooker’s 1974 album, Free Beer and Chicken, not to mention “Revolution Blues” from Neil Young’s On the Beach album, and it’s hard not to think to yourself at this point in the record what a debt Young might owe to Kershaw for the reputation of the most critically acclaimed piece of work of his career as the palpably honey-slid “Sweet Peace of Mind” lollops in after it, with a beautiful pedal steel from Elvis Presley and Dolly Parton go-to session guy Weldon Myrick. There’s a little Buck Owens-style, shit-kickin’ country thrown into the album for good measure in the form of “The Country Boy” and you can almost picture Kershaw in a rhinestone-studded Nudie suit as he croons, “There were bright lights, faster women/Things were happening all around,” before the album enters its final phase with yet another scuzzbucket jammer that feels like it could have been lifted right out of the ditch trilogy.”

“I’m going to Louisiana” opens with a loose pentatonic lick on acoustic 12-string from Charlie Daniels before being counted in with a percussive, machine gun bass from Tim Drummond – yet another soon-to-be Neil Young collaborator (Drummond went on to play on Harvest, Time Fades AwayOn The Beach, Tonight’s The Night, Zuma and more Young classics). It swings on a loose, almost unhinged, rhythm that provides a framework within which Daniels and Rhodes pianist Bob Wilson (who played extensively with Earl Scruggs as well as on Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline album and was a renowned record producer) are able to provide chugging stabs of color and texture that veritably scrape the clouds. The aforementioned “Bad Luck Blues” follows and the album ends with the dark, repetitive, droning, fiddle-heavy, mid-tempo booty-call of “Do Me Right Now” – a near-satanic paean to fornication that stays low and slow all the way to the end, at which point, Kershaw’s voice reaches high into the belting zone and rides us out on a wave of sin.”

Nick laments, “As Hidden Gems go, it’s almost unbelievable that R…CitBC is not better known. But Kershaw, for whatever reason (and believe me, I’ve Googled it), just didn’t follow up on it. Not until 1992, that is, when producer Rob Fabroni dragged him out of retirement, paired him with Neil Young and made a tantalizingly excellent second solo album called Now & Then. If only he’d made another 20 albums in between, I think the swamp rock soundscape would have been a much richer place. Rusty Kershaw died of a heart attack in 2001 and left the world with just two examples of his wonderful tenor voice and ear for grimy ditch music. Copies of the first one appear to be scarce and I’ve seen them go for a lot of money on Discogs (I was lucky enough to pick mine up for a song). So I hope this lengthy endorsement of what I think is one of the truly great undiscovered classics goes some way toward earning it a reissue. In the meantime, happy digging.”

Buy it HERE.