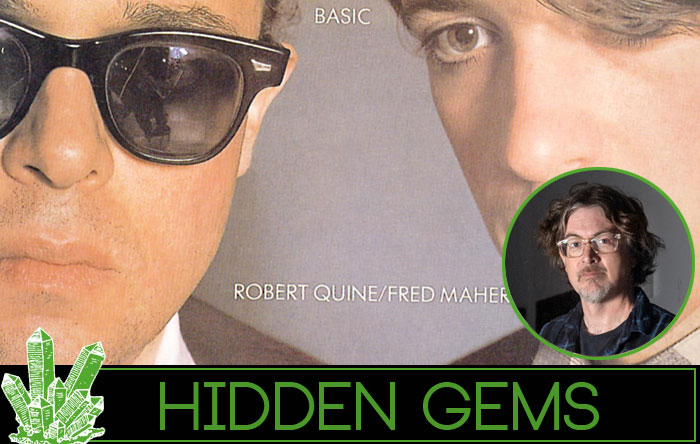

Chris Forsyth on Robert Quine & Fred Maher – Basic

Over the past few years there have been few guitarists as singular and intriguing in moving the needle forward as Chris Forsyth. As I’ve mentioned in the past, he aims for some sort of ragged, ozone-blasted bliss and always come up shaking off the cinder and ash of sonic debris. He’s exactly the sort I’m always looking for with Hidden Gems – an artist with a perspective informed by years of carving through likeminded stringsmiths to better his feel for the instrument. Its no surprise that when asked what record was sorely overlooked he found solace in another singular guitarist, but his pick is as off the path of usual touchstones as one might hope. Picking a out a piece of Robert Quine’s history, Chris opts for an oft overlooked collaborative record from 1984 with Fred Maher. Check out how this came into his life and what impact the record and Quine have had on his music.

One of the best things I’ve ever done in my life is ’65’ (from Basic) – it reflects how I feel about music with that Lester Young thing with the sadness. If people don’t appreciate the damn thing, I have no interest in banging my head against the wall…People say ‘You should put out five or six records a year.’ But ask them ‘What’s your favorite track off Basic?’ and they just look at me. There’s very few people who like those records.

“When I lived in New York City,” Forsyth recalls, “I used to bring my guitars to Rick Kelly at Carmine Street Guitars for set ups and fixes. Rick did fine work and I eventually bought one of his beautiful custom handmade Strat-style guitars, but my real motivation for going there was because more often than not, Robert Quine could be found hanging out in the shop, smoking cigarettes, playing guitar through a little practice amp, and… bitching about something. Even back around the turn of the century, Rick’s shop was a bastion of the already rapidly disappearing Old New York, and Quine’s aura was quintessentially Old New York – hard, cynical, prickly, and darkly funny. I figured “If Quine comes here, so should I.””

“For me, Quine always stood apart from the other great guitarists of the CBGB’s scene – he was a very different flavor than the austere romanticism of Television or the L.A.M.F. junkie chic of Johnny Thunders. I’ve always heard something beyond genre in Quine’s playing – something older, less contrived, more elemental. His wildly personal combination of early rock n roll riffs, unhinged free jazz-isms, and pure ambience was a one of a kind style that somehow seemed to sit perfectly in whatever context it was placed, from the Voidoids to Lou Reed’s band to Downtown collaborations with the likes of Marc Ribot and Ikue Mori.”

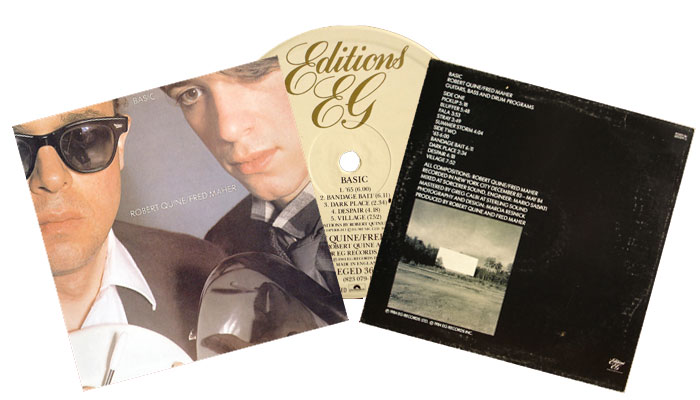

“Which brings me to Basic,” Chris concedes, “his collaboration with drummer/producer Fred Maher: one of the very few records on which he is co-leader and not credited as “just” a sideman. Quine and Maher are each credited with “Guitar/Bass/Drum Programs” on the sleeve. I first picked it up on CD at Kim’s Music in Manhattan in the late ‘90s and I love this record. However, I know a fair number of Quine heads who lionize Quine’s work with the Voidoids and Reed, but also cannot bear to listen to Basic, a phenomenon Quine himself acknowledged in the 1997 Perfect Sound Forever interview quoted above.”

“A reason for this, I think, may be that Quine was a far deeper musician than even his most ardent fans give him credit for, with an artistry that went way beyond playing haywire punk lead breaks as the mysterious foil to charismatic frontmen (though few did it better). Quine’s scope was much more broad; creating a true synthesis of influences, like Reed or Miles or Eno or Joni. These types of artists don’t conform to genre, they change them. There’s a perversity to their choices – concepts that can seem almost antagonistic in their own time (think Metal Machine Music, Get Up With it , Hissing of Summer Lawns, or On Land ) but now seem prescient, visionary. Basic is a “smaller” record than those, not a grand statement in the world of popular music, but I would include it alongside those records for sheer iconoclasm and contrariness.”

“That said,” admits Chris, “it’s not entirely without precedent in Quine’s oeuvre. His 1981 collaboration with Jody Harris, Escape, is a similarly cantankerous fusion of drifting guitar atmospherics, filtered bass funk, and arch drum programming. That record feels magnificently unhinged, as if he and Harris were throwing musical noodles at the wall and seeing what stuck. Basic feels more refined. It has higher production values (presumably via Maher), better detail in the drum programming, and more developed song structures. But still, I’ve put Basic on the turntable and had people ask if it was a warped “Beverly Hills Cop” soundtrack, possibly played at the wrong speed. True, the drum machines and some of the guitar sounds are superficially pretty locked in to a mid-‘80s vibe, but no more so than, say, Bert Jansch’s guitar sound or Bootsy Collins’ bass sound date a record to the ‘60s or ‘70s. Still, upon repeated listens, this record proves itself, like most great records, to both truly embody and transcend it’s era.”

“The guitar playing on Basic is magnificent and it ranges far and wide. It’s conceptually virtuosic without being technically flashy. There’s zombie-fied Blade Runner blues, Pete Cosey-esque wobbly rail feedback excursions, moody ambient drift that sounds uncannily like Loren Connors or some of My Bloody Valentine’s ravier moments, and just mountains of super scratchy, dry rhythm guitar funk underneath it all.”

“Basic was a major influence on my forthcoming CD/2xLP All Time Present,” notes Forsyth, “especially on the track “Techno Top,” which is all about foregrounding rhythm, timbre, repetition, and duration and burying rote guitar heroics in much the same way that Basic does for me. As a lead guitarist making mostly mostly instrumental music, I spend a lot of time thinking about how to make guitar music that can contain multitudes without coming off as wanky or cliched. It’s hard! I want to take an idiom – rock – that traditionally has a focus on vocals, and re-center other aspects of the music, de-emphasizing the voice and making the peripheral elements of the music the focal point (again: rhythm, timbre, repetition, duration). This is what John Fahey did with the blues (there wasn’t really non-vocal instrumental blues music before him). t’s also what Quine does on Basic . That’s why I consider it a true Hidden Gem.”

Honestly, I too was lacking in knowledge of Quine’s collaboration with Maher, making the same mistake Forsyth and Quine himself note in lionizing his work with Hell and Reed and even Matthew Sweet before delving into his ‘80s works, but I’ve become a convert. The record is unfortunately not as widely available, but a little Discogs digging ought to net you one at a nice price. Nab one now and dig the vibe before Forsyth’s All Time Present comes out next week. It’s already shaping up to be one of the heavy-hitters of 2019 and comes highly recommended.