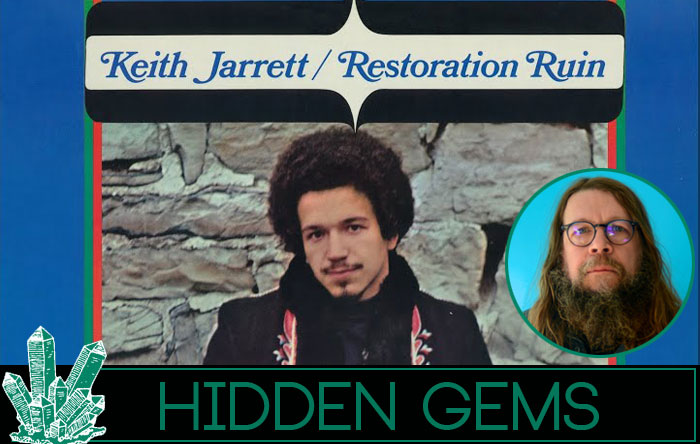

Jeffrey Alexander on Keith Jarrett’s – Restoration Ruin

Among the artists that dominated RSTB last year, Jeffrey Alexander was one of the most prolific, showing up with Dire Wolves (in one of their best yet), on a solo jaunt for Feeding Tube, and playing the RSTB anniversary show with a new group dubbed The Heavy Lidders. The latter featured members of Elkhorn and Bardo Pond laying waste to the blues in fine fashion. In anticipatetion for Dire Wolves’ latest album, on the way next month from Centripetal Force, Jeffrey’s contributed a pick to the Hidden Gems series. Picking out an oddity in the typically jazz-centric catalog of Keith Jarrett, he sheds some new light on an often maligned piece of the artist’s repertoire. Check out how this record came into Alexander’s life and what makes it such a treasure.

“On March 12, 1968 Keith Jarrett walked into Atlantic Recording Studios in New York City and recorded a new solo LP for the Vortex label,” begins Alexander. “He was already a well-known jazz pianist and improviser at this point, having toured internationally with Art Blakey’s New Jazz Messengers and Charles Lloyd Quartet. But instead of fluid piano improvisations, these were two-minute acoustic guitar-based folk-pop songs With lyrics. And he’s singing. What? This is not jazz. What’s going on here? Additionally, he overdubbed himself playing all the instruments, including harmonica, bass, drums and percussion. The only sounds on the LP not performed by Keith Jarrett are from a string quartet, featured on three of the ten tracks. It’s such an oddity in his catalog, especially when you consider that just a few months before, he was skronking some free jazz sax along with Larry Coryell for Bob Moses’ Love Animal sessions. His first solo LP for Vortex – a straight Bill Evans-esque jazz trio with Charlie Haden and Paul Motian – was also recorded at this time. By 1969 he had joined Miles Davis’ sprawling fusion ensemble on organ and electric piano. Although Jarrett’s work was quite diverse at this point, his folk era was short lived.”

“The songs themselves,” admits Jeffrey, “embody a startling freewheeling Summer Of Love sunshine hippie vibe How did this happen? One track reminds me of Tim Buckley covering Incredible String Band, another could be Pentangle playing bossanova, a few are fake Dylan outtakes, others masquerade as Arthur Lee and Love demos. It’s almost like a cover album of all-original material. When he jumps into his ‘Dylan’ tunes, it’s especially shocking. To say he wears his influences on his sleeve would be an understatement – and what colorful sleeves they are! Just dig on that album cover, brother.”

“I first heard Restoration Ruin, recalls Alexander, “in 1999 or 2000 when I was working at In Your Ear Records in Providence RI. It was a great shop with a small staff of musicians from bands like Combustible Edison, Plan 9, Emergency Broadcast Network, Sunburned Hand of The Man, and others. We would often joke about our disparate sounds, as you would expect from cantankerous record store dudes, and one day the owner Chris Zingg teased me with a ‘bootleg of unreleased Nick Drake.’ My band at the time, The Iditarod, was deeply into psychedelic folk sounds, so of course I was interested. The first notes hit the spot alright, but the vocals were definitely not Drake, what gives? Sure we all had a good laugh, but the more it played, the deeper I went with it. Restoration Ruin is certainly a product of its time, with a sort of innocent childish quality that I’m sure turns many people off. But hey, I like Donovan too,” he scoffs

“The groovy rainbow child vibe here is absolutely the result of Jarrett’s time spent in San Francisco during his three-year stint with Charles Lloyd Quartet. The quartet played extended, extremely well-received engagements at the Avalon and Fillmore, including two live albums, Love-In and Journey Within, both recorded on January 27, 1967. This was less than two weeks after the Human Be-In / Gathering Of The Tribes in Golden Gate Park, which Jarrett enjoyed as well. The quartet also befriended and played with The Grateful Dead at the Rock Garden, a club in the Outer Mission (a few blocks down from my old apartment, by the way). They also played the Dead’s debut show at Berkeley’s Greek Theater (one of my all-time favorite venues).”

“In his 1999 book Garcia: An American Life, Blair Jackson writes:

‘The New York-based Charles Lloyd Quartet was a significant force in the San Francisco scene because they managed to make free-ranging improvisational jazz that was accessible to rock fans. Lloyd’s band, which, besides the talented reedsman, included pianist Keith Jarrett, drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Cecil McBee, was one of the first jazz groups to be invited to play the Fillmore, and Lloyd jammed with the Dead at the Human Be-In, adding breathy flute to a long workout on “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl.” It was Garcia’s idea to book Lloyd’s group at the Rock Garden, and he was such a fan of the group that when he and Phil Lesh appeared on Tom Donahue’s KMPX radio program as guest deejays in April 1967, one of the songs he chose to play was Lloyd’s trippy “Dream Weaver,” a potent dose of acidy jazz from late 1966 that presaged some of the free-floating but intense places the Dead’s music would go in the last part of 1967 and early 1968. “Dream Weaver” is a sort of proto—“Dark Star,” complete with passages of spellbinding dissonance andgently cascading melody streams.’”

“This is an astonishing passage,” gushes Alexander. “I encourage everyone to listen to ‘Dream Weaver: Meditation/Dervish Dance’ by Charles Lloyd and pay specific attention to Keith Jarrett’s winding piano lines. This was recorded March 20, 1966 – a year later they would be alternating sets with the Dead, who were, at that time, in the process of birthing ‘Dark Star.’ Charles Lloyd continues in Blair Jackson’s book: “I think we probably influenced them a bit to start opening up their improvisations. When we were at the Rock Garden, we traded sets and they’d all be hanging around in the wings when we played, really listening. Jazz has always been a music of freedom and inspiration and wonder and consolation, and the Dead definitely got something from that.”

“It’s fascinating to me,” remarks Jeffrey, “that they turned so many hippies in the ballroom scene onto jazz. In return, Jarrett put flowers in his hair, if only for a minute. I can almost picture Keith Jarrett there in the park, wearing a bright orange Nehru jacket with a bunch of dogs running around, incense burning, Allen Ginsberg blowing on an ocarina, because of course he is. And it’s not the silliness of the flower power scene that I’m romanticizing, it’s the free spirited vibes that, remarkably, still endure in that place (meth and Whole Foods be damned). It must be that magical San Francisco sunshine.”

“In the liner notes to his 2013 CD No End (recorded in 1986), Keith Jarrett writes ‘I was a participant in Haight-Ashbury during the golden days of hippiedom.’ He continues on to describe hanging out in Golden Gate Park with his soprano sax: ‘Some of the players were not so good, but it didn’t really matter; it was the ‘intent’ that counted. People walked by and listened or not. It was a rare kind of freedom.’ It’s this looseness that I find so appealing about Restoration Ruin,” notes Jeffrey. “I embrace that looseness in my own music, especially with Dire Wolves Just Exactly Perfect Sisters Band. Our jams are about feeling and listening and being in the moment, getting lost in the music, improvising together. I also really appreciate the unexpected amalgam of genres — both free and straight-ahead jazz, rock fusion, relaxed improvisation, and singer-songwriter sounds that Keith Jarrett produced from 1967-1971. It was quite a far-reaching run of work that resonates with me and the music I create very much. Many of my far-flung influences such as avant folk, astral jazz, and kosmische rock are a blend of these varied ingredients.”

It’s totally ironic that the only two guitar-centric Keith Jarrett albums – Restoration Ruin and No End – are both my favorites and also the most hated by Keith Jarrett fans. In his 2014 review of No End in Jazz Times, Michael J. West writes: “… 90-plus minutes of droning, ’60s-ish psychedelic jams. Forget one-man bands; Jarrett is a one-man drum circle. There’s little more to it than that. Jarrett claims in his liners that his only premeditation for the music was “groove”; alas, variety and direction seem to have been among the casualties. “XVII,” for example, consists of two rotating pairs of guitar chords, each a whole tone apart, brief single-note noodles (with the vaguely Eastern flavor that was popular with the likes of Jerry Garcia) in between, and loping four-to-the-bar percussion underneath. And, of course, Jarrett’s grunting vocalizations. Perhaps Jarrett recorded No End out of nostalgia for working in Charles Lloyd’s and Miles Davis’ bands-days beguiling the hippie set, who found virtue in aimless jamming.”

“I don’t know man, it sounds pretty great to me,” concludes Alexander. It’s interesting that Jarrett takes this vibe and channels it into mellow, semi-orchestrated poppy folk music on Restoration Ruin. Imagine if he had spread those songs out with some of the extended jamming and improvisation found on No End or some of those Charles Lloyd LPs. Merging those elements would have been incredible, the best of both worlds. Instead, the styles Jarrett embraced in that period jumped as much as the track by track influences on Restoration Ruin I dig it all though.”

Support the artist. Buy it HERE.