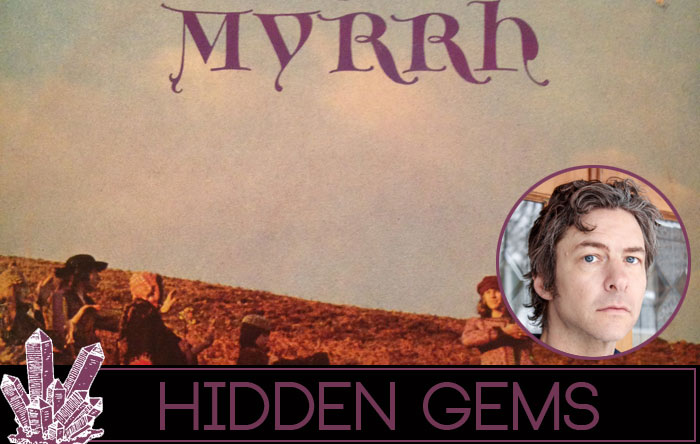

James Elkington on Robin Williamson – Myrrh

You might not immediately recognize James Elkington’s name but chances are you’ve heard his playing on songs by Jeff Tweedy, Wooden Wand, Richard Thompson, Steve Gunn, Michael Chapman, Joan Shelley, Nathan Salsburg or Tortoise. He’s a kind of sidmean’s sideman, a songwriter’s secret weapon who adds texture and depth to any song he graces. He’s steeped in the traditions of Basho, Fahey and Ayers with a touch that rivals his compatriot Steve Gunn in accessibility and nuance. As usual Hidden Gems explores the albums that inspire reverence in artists, the ones that they feel haven’t received due diligence. Elkington goes deep on a solo outing from the Incredible String Band’s Robin Williamson, and makes a case for a psych-folk classic lost to time.

James explains how Myrrh seeped its way into his life, “My road to The Incredible String Band was highly convoluted, and I came to them a lot later than I should have. The British folk revival of the 1960’s was somewhat reviled by my generation growing up in the 1980’s, but the ISB appeared to be from the more hip and acid-tinged fringes of that scene, and I’d often see their album, The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter, sharing space with my friends’ Fall and Felt albums. Fast-forward about 10 years, and I found that my first steps into songwriting and guitar-playing had more parallels with the folkies than I imagined; that kicked off a huge re-evaluation of folk music for me that still continues today.

“Bert Jansch and Pentangle quickly became my favorites” Elington confesses, “but records by C.O.B., Martin Carthy and Nic Jones were in regular rotation and I was having a ball. I’d been listening to the ISB for a little while when I discovered that the two main members had briefly gone their separate ways in 1971 to make solo albums. Now, I’ve always been a sucker for a solo record or a side-project – having played in bands all my life, I’ve always been fascinated by musicians who find themselves working on their own after having worked in a band context for years. What do they do with all that freedom? I’ve always suspected that what makes the first rash of Beatles solo albums so interesting is the sudden absence of the other three Beatles, and I’ve always loved the solo records by Kevin Ayers and Jack Bruce for the same reason. The initial rush of freedom that comes from someone working outside the committee for the first time always sounds so inspiring – its energy I can always use.”

Of the two ISB records to be come out in 1972″ says Elkington, “Mike Heron’s Smiling Men With Bad Reputations is by far the better known – a departure from the ISB’s runic ramble, Smiling Men… is a straighter rock-based affair, with appearances by such luminaries of the 70’s rock pantheon as Pete Townsend and John Cale. Myrrh, by contrast, was much more like the ISB in feel, and was as such relegated to Island Records’ mid-price imprint, ‘Help’ (presumably because the ISB wasn’t that big of a seller in itself, and that they assumed Williamson by himself would need “help”). But the single-mindedness and tighter scope of Myrrh lends itself a focus and continuity that I’ve never been able to find in his more famous group – from the seasick violins of “Strings In The Earth And Air? to the plaintive mandolins and bar-room blues of “I See US All Get Home,” the intimate production makes you feel as if every song is being performed from an as yet undiscovered room in your own house. The free-wheeling “The Dancing Lord Of Weir” looks back to the ISB’s best material, but there are stylistic stretches too – “Rend-Moi Demain? is a convincing piece of Yves Montand-style chanson, and “Sandy Land” wouldn’t have been out of place on Traffic’s John Barleycorn Must Die – and yet the whole thing hangs together so well as being Williamson’s unique vision.”

“I’ve already taken up too much of your time prattling on about this record, but I love it! Whenever I see its cover, with its Wicker Man band of raggle-taggle loafers trekking across the glen, it makes me want to up and join them. And it may be that I’ve forged some sort of personal relationship with Myrrh that you discerning readers won’t be able to fathom, but isn’t that what this column’s all about?”

That’s precisely what this column is about, and Elkington raises some great points about Williamson’s solo outing. It’s never received the reverence of ISB’s main material, and that’s a shame. For what it’s worth, the album is a grand example of what was inherently right about the ’70s psych-folk boom. While it’s not a title that’s seen the hunger of reissue, it can be had for a very accessible price on the secondary market. As for Elkington, his album, Wintres Woma, arrives at the end of the month via the venerable Paradise of Bachelors.

Support the artist. Buy it HERE.